ABE has launched the long-anticipated pilot version of our updated Exploring Precision Medicine curriculum module for upper-level secondary students. This module takes a deep dive into the concept of precision medicine—an emerging approach to health management that tailors treatment and prevention strategies to an individual’s genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

As an introduction to the module, we are excited to share a short, engaging hands-on mini-lab that gives students a “taste” of the module—an activity that explores why people differ in their abilities to detect bitterness in food.

The Bitter Truth About Our Sense of Taste

You may be surprised to learn that our ability to taste bitterness is strongly influenced by our genes—and that the discovery traces back to a laboratory accident almost a century ago. In 1931, DuPont chemist Arthur Fox was working with a compound called phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) when he accidentally released some into the air. As the PTC dust swirled around the lab, a nearby colleague remarked that it tasted bitter. Fox was surprised because he did not taste anything at all. Intrigued, he began offering small samples to colleagues, friends, and family.

Fox soon discovered striking differences in people’s reactions to the taste of PTC: some tasted nothing, some noticed only a mild bitterness, and others found the taste unbearably bitter. These observations ultimately led to the discovery that differences in taste perception have a genetic basis. One gene in particular—Taste Receptor 2 Member 38 or TAS2R38—plays a key role in detecting bitterness. Humans carry two versions (alleles) of this gene, and the specific combination we inherit helps determine how strongly we taste bitter compounds—shaping our food preferences and even dietary choices.

How Taste Works

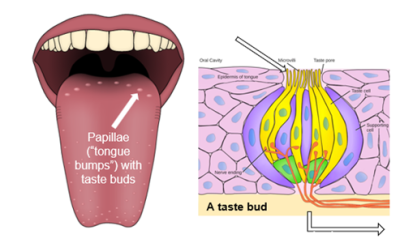

Bitterness is only one of the five tastes that humans recognize. The others are salty, sweet, sour, and umami (savory). Each taste corresponds to its own type of receptor cell located on the tongue.

When we perceive taste, chemical compounds in the foods we eat bind to the matching receptor cells, which then send signals to our brain that allow us to experience flavor. If a taste compound fails to bind to the receptor cell, we won’t perceive that taste.

So why does PTC taste bitter? PTC binds to a bitter taste receptor in taste buds on the tongues of people who are sensitive to it, sending a signal to the brain. If you find foods such as raw broccoli or Brussels sprouts particularly bitter, it’s likely that you can also taste PTC.

A Taste of Precision Medicine

The “Are You a Bitter Taster?” activity (and accompanying slides) is a modified version of a lab from the Exploring Precision Medicine module. Using PTC taste strips, the activity allows students to identify their bitter-tasting phenotype (their observable taste trait)—strong taster, weak taster, or nontaster. The only materials needed are PTC taste strips and water for mouth rinsing, making it easy to run in any classroom.

In Exploring Precision Medicine, this hidden trait—the bitter-tasting phenotype—serves as a proxy for understanding other hidden traits that can influence health, such as how an individual responds to different medications.

The New Exploring Precision Medicine Module

Curious whether Exploring Precision Medicine might be a good fit for your classroom? The “Are You a Bitter Taster?” activity offers a fun, accessible way to preview the materials. The full Exploring Precision Medicine module uses a case study, readings, videos, and laboratory exercises to help students understand how the interplay between genes and the environment shapes human traits.

Throughout the module, students investigate the implications of genetic variability for health and disease, connecting genetic differences in medication metabolism to one of their own traits—the ability to taste the bitter compound PTC. Students also explore DNA sequencing, bioinformatics, and bioethics while learning essential laboratory techniques, including DNA extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), restriction enzyme digestion, and gel electrophoresis.

Exploring Precision Medicine is designed for high school biology classrooms and ABE program sites but is available to all.